Prof Lubna Riyadh Abdul Jabarcollege of Arts Baghdad University

Early Women of Science, Technology, Medicine and Direction

This article is a paper submitted to and presented at WISE 2018: World Muslim Women's Tiptop & Exhibition, organised by TASAM, Istanbul, Turkey, from 28th Feb - quaternary March 2018.

Figure ii. Article Imprint

Figure ii. Article Imprint

Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. Women in the historiography: A problem of methodology

iii. Recent scholarship

3.i. The Muhaddithat project

three.2. Dictionary of women

4. General overview

5. Medical care

5.1. Rufayda al-Aslamiyyah

5.iii. Nusayba bint Harith al-Ansari

5.4. Women surgeons in 15thursday-century Turkey

half dozen. Mathematics

six.i. Sutayta Al-Mahāmali

7. Making of astronomical instruments

8. Patronage

8.1. Zubayda bint Abu Ja'far al-Mansur

8.2. Fatima al-Fehri

8.iii. Dhayfa Khatun

9. Rulers and political leaders

9.one. Sitt al-Mulk

9.two. Shajarat al-Durr

9.3. Sultana Raziya

ix.iv. Amina of Zaria

9.5. Ottoman women

10. Miscellanea

11. By way of a decision

12. Bibliography

Effigy 1.Professor Salim TS Al-Hassani at WISE 2018

1. Introduction

While several studies have investigated the contribution of Muslim women in various fields of the classical civilization of Islam, such as in hadith manual, jurisprudence (fiqh), literature, and didactics, until now few sources mention the role of women in the evolution of science, technology, and medicine in the Islamic tradition.

Effigy 3. A famous signed sketch of Hypatia, included as an insert in Elbert Hubbard's pamphlet Little Journeys to the Homes of Peachy Teachers, vol. 23, no 4, 1908.

In scholarship, in that location are isolated and scattered references to the famous women who had a function in advancing scientific discipline and who established charitable, educational and religious institutions. Some examples are Zubayda bint Ja'far al-Mansur who pioneered a well-nigh ambitious project of earthworks wells and building service stations all along the pilgrimage route from Baghdad to Mecca, Sutayta who was a mathematician and an expert witness in the courts, Dhayfa Khatun who excelled in direction and statesmanship, Fatima al-Fehri who founded the Qarawiyin mosque in Fez, Morocco, which became the first university in the globe, and the engineer Al-'Ijlia who fabricated astrolabes in Aleppo.

In view of the scant information on such women and the growing importance of the subject area of gender and women in society, this report presents what is currently known about their lives and works. Our aim is twofold: to present the available information and to initiate a process of investigation to unearth what could be a most pregnant find about the roles played by hundreds of women in various fields and in the different periods of Islamic history.

2. Women in the historiography: A problem of methodology

Over thousands of years, many women have left a mark on their societies, changing the course of history at times and influencing minor but significant spheres of life at others. Since aboriginal times, women have excelled in the areas of poetry, literature, medicine, philosophy and mathematics. A famous example is Hypatia (ca. 370-415), a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, and instructor who lived in Alexandria, in Hellenistic Arab republic of egypt, and who participated in that city's educational community. [1]

Figure 4.Cleopatra VII and her son Caesarion at the Temple of Dendera (Source)

In the same vein, information technology is interesting to notation the Islamic view of Cleopatra of Egypt (b. 69 BCE). Arabic sources referred to her every bit a strong and able monarch who was very protective of Arab republic of egypt. These sources focused on her talents but made no reference to her morals or seductive ability. They focused instead on her learning and talents in management. This Arabic image of Cleopatra is in directly contrast to that presented by the Greco-Roman sources which presented her as a hedonist and seductive woman. [2]

From the early years of Islam, women had crucial roles in their club. They contributed substantially to the prominence of Islamic civilization. For example, Aisha bint Abu Bakr, wife of the Prophet Muhammad, had special skills in assistants. She became a scholar in hadith, jurisprudence, an educator, and an orator. [iii] There are as well many references which point to Muslim women who excelled in areas such equally medicine, literature, and jurisprudence. This long tradition establish its counterpart in modern times. For example, in a more recent and unusual function, Sabiha Gökçen (1913-2001) was the get-go female gainsay pilot in the world. She was appointed as chief trainer at the Turkish Aviation Institution. [iv]

In contrast, nosotros find little data on Muslim women's contributions in the classical books of history. New lite might arise from the report of not yet edited manuscripts. There are about five one thousand thousand manuscripts in archives effectually the world. Just about 50,000 of them are edited and most of these are not nigh science. [5] This points to the challenging task lying alee for researchers into the subject.

Figure 5. A Turkish banknote dated thirty Baronial 1995 to celebrate Sabiha Gökçen (1913-2001), the first female combat pilot in the earth and the beginning Turkish aviatrix (Source) (Source)

iii. Recent scholarship

However, this traditional trend is changing in contempo scholarship. Some recent works endeavour to rehabilitate the role of women in Islamic history. Two examples of such works are presented beneath.

iii.1. The Muhaddithat project

For several years, Dr Mohammed Akram Nadwi conducted a long term and large scale project to unearth the biographies of thousands of women who participated in the hadith tradition throughout Islamic history. In Al-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam, [6] Dr Nadwi summarized his twoscore-volume biographical lexicon (in Standard arabic) of the Muslim women who studied and taught hadith. Even in this short text, he demonstrates the central function women had in preserving the Prophet'due south teaching, which remains the master-guide to understanding the Qur'an equally rules and norms for life. Within the bounds of modesty in dress and manners, women routinely attended and gave classes in the major mosques and madrasas, travelled intensively for 'the noesis', transmitted and critiqued hadith, issued fatwas, and so on. Some of the most renowned male scholars have depended on, and praised, the scholarship of their female person teachers. The women scholars enjoyed considerable public dominance in society, non equally the exception, merely as the norm.

Figure 6.From the 1001 Inventions Business firm of Wisdom canvas © 1001 Inventions (Source)

The huge body of data reviewed in Al-Muhaddithat is essential to agreement the role of women in Islamic gild, their past accomplishment and future potential. Hitherto information technology has been so dispersed as to be 'hidden'. The information in Dr Nadwi'southward lexicon will greatly facilitate further study, contextualization and analysis. [vii]

3.2. Dictionary of women

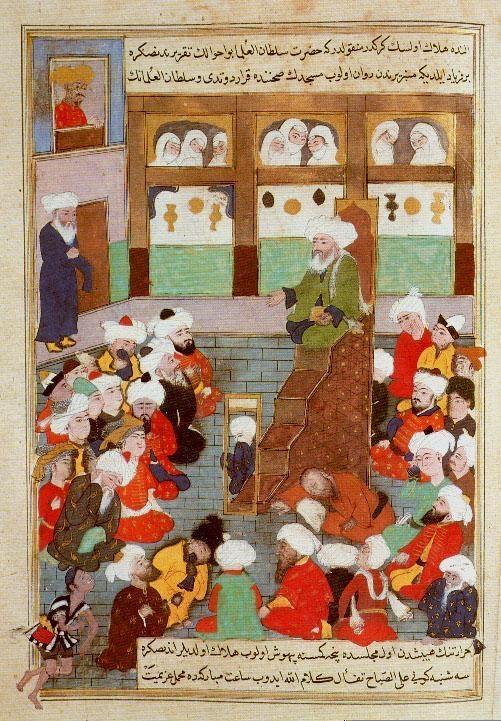

Effigy 7. From an next room, women nourish the preaching of Shaykh Baha'al-Din Veled in Balkh, Afghanistan. Miniature inJami' al-Siyar, 1600. MS Hazine 1230, folio 112a, Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul (Source)

Expanding on her work, Islam: The Empowering of Women, Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley published Muslim Women: A Biographical Lexicon. This most timely work in dictionary form is a comprehensive reference source of Muslim women throughout Islamic history from the commencement century AH to roughly the eye of the 13th century AH. A perusal of the entries shows that Muslim women have been successful, for example, as scholars and businesswomen as well as fulfilling their roles as wives and mothers for the by fourteen centuries. [8]

The writer wrote that her book originally came nigh as a response to frequent requests to provide some sources about women scholars:

"When I went through my biographical references, I was surprised by the number of references to women, and the great number of women represented in all areas of life, from scholars to rulers, whether regents or women who ruled in their own right, or women who wielded substantial political influence. This led to the decision to compile a larger source of reference of Muslim women, and, given modern views of women in Islam, information technology gives the states a surprising picture of but how active women take been in the history of Islam from the very start upwardly until the present time.

"The lexicon covers the period from the time of the Prophet to roughly the middle of the xiiith-nineteenth century. (…) As we can see by a perusal of the entries, the office of Muslim women was by no means confined to house and home. They were active in many fields. This is not a question of either/or. It is a question of many roles, all intermeshed and interlocking, rather than split categories. A concern woman is still a mother and a scholar is however a married woman. Women simply learn to juggle things more, but that is something women are very good at doing, as can exist seen by the entries.

The entries are compiled from a number of sources. Many of the biographical collections devote a section to women, like volume eight of the Tabaqat of Ibn Sa'd and al-Sakhawi's Kitab an-Nisa'. Sometimes references are found within biographies of other references. A number of notable scholars mention their teachers, who included a number of women. Ibn Hajar studied with 53 women, equally-Sakhawi had ijazas from 68 women, and as-Suyuti studied with 33 women – a quarter of his shaykhs. Al-Aghani by Abu'50-Faraj al-Isbahani is the major source for singers. An excellent modernistic source is A'lam an-Nisa' by 'Umar Rida Kahhala, which consists of 5 volumes dealing with notable women, and is by no means inclusive". [9]

Effigy 8a-b. Two views of the Firdaws Mosque and Madrasa in Aleppo built by Dayfa Khatun in 1235-36 CE (Source)

iv. General overview

The eminence attained by many women in Islamic civilisation begins to be unveiled in contempo scholarship. The female relatives of the Caliphs and courtiers vied with each other in the patronage and tillage of messages. Ayesha, the daughter of Prince Ahmed in the Andalus, excelled in rhyme and oratory; her speeches aroused the tumultuous enthusiasm of the grave philosophers of Cordoba; and her library was one of the finest and near complete in the kingdom.

Effigy ix.Lubna of Cordoba by José Luis Muñoz (Source)

Wallada (known as Valada in Western scholarship), a princess of the Almohads, whose personal charms were not inferior to her talents, was renowned for her knowledge of poetry and rhetoric; her conversation was remarkable for its depth and brilliancy; and, in the academic contests of Cordoba, the capital which attracted the learned and the eloquent from every quarter of the Iberian Peninsula, she never failed, whether in prose or in poetical limerick, to out-distance all competitors.

Al-Ghassania and Safia, both of Seville, were also distinguished for poetical and oratorical genius; the latter was unsurpassed for the beauty and perfection of her calligraphy; the splendid illuminations of her manuscripts were the despair of the near accomplished artists of the historic period. The literary attainments of Miriam, the gifted daughter of Al-Faisuli, were famous throughout the Andalus, the caustic wit and satire of her epigrams were said to accept been unrivalled.

Umm al-Sa'd was famous for her familiarity with Muslim tradition. Labana of Cordoba was thoroughly versed in the exact sciences; her talents were equal to the solution of the nearly complex geometrical and algebraic issues, and her vast acquaintance with general literature obtained her the important employment of private secretary to the Caliph Al-Hakam Two.

In AI-Fihrist, Ibn al-Nadim names women with a varied range of skills. Two are grammarians — a much respected branch of knowledge, related to the use of the total range of excellence of the Arabic linguistic communication. At that place was a woman scholar of Arab dialects, "whose origin was amidst the tribes", and another "acquainted with tribal legends and colloquialisms". A third wrote a book entitled "Rare forms and sources of verbal nouns". Aspiring poets, like Abu Nuwas, used to spend time with the desert tribes to perfect their noesis of pure Arabic. In a different field, Arwa, "a woman known for her wise sayings", wrote a book about "sermons, morals and wisdom".

Figure x. Anonymous oil painting portrait, now located at Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, of Hürrem Sultan or Roxelana (c. 1510 – Apr eighteen, 1558), the wife of Süleyman the Magnificent, known for her charities and engagement in several major works of public building, from Mecca to Jerusalem and in Istanbul (Source)

The making of astrolabes, a branch of engineering of great status, was practiced past one woman, Al-'Ijliyah bint al-'Ijli al-Asturlabi, who followed her father's profession in Aleppo and was employed at the courtroom of Sayf al-Dawlah (333 H/944 CE-357/967), ane of the powerful Hamdanid rulers in northern Syrian arab republic who guarded the frontier with the Byzantine empire in the tenth century CE.

In the development of the fine art of calligraphy, one woman at least took part. Thana' was a slave in the household of the tutor to one of the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mansur's sons. This tutor, Ibn Qayyuma, seems to take been a dedicated teacher, for the young slaves in his household benefited equally well equally his royal educatee. Of the two whom he sent to be trained by the leading calligraphist of the day, Ishaq ibn Hammad, one was the girl Thana'. His pupils, says Ibn al-Nadim, "wrote the original measured scripts never since equaled." [10]

We now present brief information on women who excelled in medicine, mathematics, astronomy, instrument making and patronage, as examples for future research and further investigation.

5. Medical intendance

Throughout history and fifty-fifty as early every bit the time of Prophet Muhammad, there are examples of Muslim women making significant contributions to the improvement of the quality of the social and economic life of their societies. They actively participated in management, education, religious jurisprudence, medicine and health as they were motivated by their concern for the diplomacy of the people. The Sharia (Islamic constabulary) requires Muslims to have great concern for society in all spheres of life. Thus, throughout Islamic history the search for scientific knowledge was considered as an human action of worship. With the arrival of Islam women were able to do every bit physicians and treat both women and men particularly on the battlefields. Nevertheless, the strict segregation between men and women meant that women had footling or no contact with men outside their firsthand family. So the healthcare of Muslim women was mainly handled by other women, particularly every bit it was socially improper for a man to attend a woman regarding matters of her health. The following are some examples of some of Muslim women who contributed to the advancement of medicine.

The title of the first nurse of Islam is credited to Rufayda Bint Saad Al Aslamiyya. But names of other women were recorded as nurses and practitioners of medicine in early on Islam: Nusayba Bint Kaab Al-Mazeneya, ane of the Muslim women who provided nursing services to warriors at the battle of Uhud (625 H), Umm Sinan Al-Islami (known also as Umm Imara), who became a Muslim and asked permission of the Prophet Muhammad to become out with the warriors to nurse the injured and provide water to the thirsty, Umm Matawe' Al-Aslamiyya, who volunteered to be a nurse in the ground forces later on the opening of Khaybar, Umm Waraqa Bint Hareth, who participated in gathering the Quran and providing her nursing services to the warriors at the battle of Badr.

5.1. Rufayda al-Aslamiyyah

Rufayda bint Sa'ad, also known as Rufayda al-Aslamiyyah, considered the showtime nurse in Islamic history, lived at the fourth dimension of the Prophet Muhammad. She nursed the wounded and dying in the wars with the Prophet Muhammed in the battle of Badr on 13 March 624 H.

Rufayda learnt most of her medical knowledge by assisting her father, Saad Al Aslamy, who was a doc. Rufayda devoted herself to nursing and taking care of sick people and she became an skilful healer. She adept her skills in field hospitals in her tent during many battles equally the Prophet used to club all casualties to be carried to her tent so that she might treat them with her medical expertise.

Figure eleven. Two Andalusian Arab women playing chess, with a girl playing lute (Chess Problem #19, F18R) , from Alphonso X'sBook of Games (Libro de los Juegos). The book was deputed betwixt 1251 and 1282 CE past Alphonso X, King of Leon and Castile. Information technology reflects the presence of the Islamic legacy in Christian Spain. Information technology is now housed at the monastery library of St. Lorenze del Escorial (Source)

Rufayda is depicted as a kind, empathetic nurse and a good organizer. With her clinical skills, she trained other women to be nurses and to work in the surface area of health care. She also worked as a social worker, helping to solve social problems associated with disease. In addition, she helped children in need and took care of orphans, handicapped and the poor. [eleven]

v.2. Al-Shifa bint Abduallah

The companion Al-Shifa bint Abduallah al Qurashiyah al-'Adawiyah had a strong presence in early on Muslim history as she was one of the wise women of that fourth dimension. She was literate at a fourth dimension of illiteracy. She was involved in public assistants and skilled in medicine. Her real name was Laila, yet "al-Shifa", which means "the healing", is partly derived from her profession every bit a nurse and medical practitioner. Al-Shifa used to use a preventative treatment against pismire bites and the Prophet canonical of her method and requested her to railroad train other Muslim women. [12]

5.3. Nusayba bint Harith al-Ansari

Nusayba bint Harith al-Ansari, also called Umm 'Atia, took care of casualties on the battlefields and provided them with water, nutrient and commencement aid. In addition, she performed circumcisions. [thirteen]

5.iv. Women surgeons in 15th-century Turkey

Between those first names of early Islamic history other women proficient medicine and nursery. Few of them were recorded. However, a serious investigation in books of history, of medicine and literature writings will certainly provide precise information nigh their lives and achievements.

In the fifteenth century, a Turkish surgeon, Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu (1385-1468), author of the famous manual of surgery Cerrahiyyetu'l-Haniyye, did not hesitate to illustrate the details of obstetric and gynaecologic procedures or to depict women treating and performing procedures on female patients. He too worked with female surgeons, while his male colleaques in the Due west reported against the female person healers.

Female surgeons in Anatolia, generally performed some gynaecological procedures similar surgical managements of fleshy grows of the clitoris in the female ballocks, imperforated female pudenda, warts and red pustules arising in the female person pudenda, perforations and eruptions of the uterus, abnormal labours, and extractions of the aberrant foetus or placenta. Interestingly in the Cerrahiyyetu'50-Haniyye, nosotros observe illustrations in the forms of miniatures indicating female surgeons. It can therefore be speculated that they reflect the early recognition (15th century) of female person surgeons with paediatric neurosurgical diseases similar foetal hydrocephalus and macrocephalus.

The attitudes towards women in the history of medicine reflect the full general view that society held of women during the menses. Information technology is interesting that in the treatise of Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu we find an open minded view of women, including female person practitioners in the circuitous field of surgery. [xiv]

half dozen. Mathematics

In the field of mathematics, names of female scholars featured in Islamic history such as Amat-Al-Wahid Sutaita Al-Mahamli from Baghdad and Lobana of Cordoba, both from the xth century. Systematic investigation, with the methodology of history of science, will certainly yield more data on other women scholars who expert mathematics in Islamic history. We know of many women who practiced fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). Now, calculations and arithmetic were intertwined with successoral calculations (fara'idh and mawarith), a branch of practical mathematics devoted to performing calculatations of inheritance according to the rules of Islamic law.

half dozen.ane. Sutayta Al-Mahāmali

Sutayta, who lived in the 2nd one-half of the 10th century, came from an educated family from Baghdad. Her father was the judge Abu Abdallah al-Hussein, writer of several books including Kitab fi al-fiqh, Salat al-'idayn. [15] Her uncle was a Hadith scholar and her son was the judge Abu-Hussein Mohammed bin Ahmed bin Ismail al-Mahamli who was known for his judgements and his talents.

Sutaita was taught and guided by several scholars including her father. Other scholars who taught her were Abu Hamza b. Qasim, Omar b. Abdul-'Aziz al-Hashimi, Ismail b. Al-Abbas al-Warraq and Abdul-Alghafir b. Salamah al-Homsi. Sutayta was known for her skilful reputation, morality and modesty. She was praised past historians such equally Ibn al-Jawzi, Ibn al-Khatib Baghdadi and Ibn Kathīr. [xvi] She died in the year 377H/987CE.

Effigy 12. View into the courtyard towards the prayer hall of the Qarawiyyin mosque and university in Fez (photograph date 1990, copyright Aga Khan Visual Annal, MIT) (Source)

Sutayta did not specialize in merely one subject area but excelled in many fields such as Arabic literature, hadith, and jurisprudence as well as mathematics. It is said that she was an expert in hisab (arithmetics) and fara'idh (successoral calculations), both being practical branches of mathematics which were well developed in her time. Information technology is said also that she invented solutions to equations which have been cited by other mathematicians, which denote aptitude in algebra. Although these equations were few, they demonstrated that her skills in mathematics went across a elementary aptitude to perform calculations.

6.2. Labana of Cordoba

Labana of Cordoba (Espana, ca. 10th century) was one of the few Islamic female mathematicians known by proper name. She was said to exist well-versed in the exact sciences, and could solve the most complex geometrical and algebraic problems known in her time.

Her vast associate with general literature obtained her the of import employment of individual secretarial assistant to the Umayyad Caliph of Islamic Spain, al-Hakam Ii. [17]

7. Making of astronomical instruments

In astronomy and related fields, the historical records kept but one proper noun, that of Al-'Ijliya, apparently an astrolabe maker. Picayune information is available about her, and we know of simply 1 source in which she is mentioned, the famous bio-bibliographical work Al-Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadim.

In department VII.2 (data on mathematicians, engineers, practitioners of arithmetic, musicians, calculators, astrologers, makers of instruments, machines, and automata), Ibn al-Nadim presents a list of 16 names of engineers, craftsmen and artisans of astronomical instruments and other machines. Al-'Ijliya, of whom Ibn al-Nadim did non mention the first name, is the only female person in the list. Several of the experts thus named are from Harran, in Northern Mesopotamia, and probably Sabians, whilst others may be Christians, as information technology can be concluded from their names. At the end of the list, two entries mentioned Al-'Ijli al-Usturlabi, pupil of Betolus, "and his daughter Al-'Ijliya, who was with [significant she worked in the court of] Sayf al-Dawla; she was the pupil of Bitolus" (Al-'Ijli al-Usturlabi ghulâm Bitolus; Al-'Ijliya ibnatuhu ma'a Sayf al-Dawla tilmidhat Bitolus). [18]

The proper name of Al-'Ijli and his daughter is derived from Banu 'Ijl, a tribe which was function of Banu Bakr, an Arabian tribe belonging to the large Rabi'ah branch of Adnanite tribes. Bakr's original lands were in Nejd, in key Arabia, but most of the tribe's bedouin sections migrated northwards immediately before Islam, and settled in the area of Al-Jazirah, on the upper Euphrates. The urban center of Diyarbakir in southern Turkey takes its name from this tribe. The Banu 'Ijl, mostly Bedouin, located in al-Yamama and the southern borders of Mesopotamia. [19]

Figure thirteen. Front cover ofThe Forgotten Queens of Islam by Fatima Mernissi, translated from French by Mary Jo Lakeland (University of Minnesota Press, 1993, hardcover)

From this, albeit as well brief, quotation of Ibn al-Nadim, it turns out that Al-'Ijliya, of whom Ibn al-Nadim did non specify the first name, was the daughter of an instrument maker, and similar her begetter, they were members of a rich tradition of engineers and astronomical musical instrument makers who flourished in the 9thursday-10th century. Ibn al-Nadim mentioned her in a section on "machines" simply in it on astronomical instruments only. Therefore, we do not know if Al-'Ijliya was solely adept in this field. She worked in the court of Sayf al-Dawla in Aleppo (reigned from 944 to 967), and she was the pupil of a certain Bitolus, who taught her the secrets of the profession. Her father, and several scholars mentioned by Ibn al-Nadim, were apprentices to the aforementioned master, who seems to take been a famous astrolabe-maker. Nosotros practise not know where she was born nor if she learned musical instrument making in Aleppo or elsewhere. Among the few extant Islamic astrolabes, none bears her proper noun, and as far as the available classical sources can let u.s. to judge, she is the only woman mentioned in connection with instrument making or engineering work.

8. Patronage

Muslim women have played a major office in promoting civilization and science in the Islamic world. Some have built schools, mosques and hospitals. The post-obit are some examples of these women and their crucial touch on on Islamic civilization.

eight.1. Zubayda bint Abu Ja'far al-Mansur

Zubayda bint Abu Ja'far, the wife of Harun ar-Rashid, was the wealthiest and most powerful woman in the world of her fourth dimension. She was a noblewoman of bang-up generosity and munificence. She the developed many buildings in different cities. She was known to have embarked upon a gigantic project to build service stations with water wells all along the Pilgrimage route from Baghdad to Mecca. The famous Zubaida water spring in the outskirts of Mecca still carries her name. She was also a patron of the arts and poetry. [xx]

Figure 14. This 9.5m high conical dome with Muqarnas features on height of a iv.8m high 8 sided building in West Baghdad is popularly known as Sit down Zubayda tomb. But, historically, this mausoleum is where Zommurrud Khatun was cached

Figure 15. The Arabian Peninsula (Image Source)

8.two. Fatima al-Fehri

Fatima al-Fehri has played a groovy role in the civilization and culture in her community. She migrated with her male parent Mohamed al-Fehri from Kiroan in Tunisia to Fez. She grew upwardly with her sis in an educated family and learnt Fiqh and Hadith. Fatima inherited a considerable amount of coin from her father which she used to build a mosque for her community. Established in the yr 859, the Qarawiyin mosque had the oldest, and possibly the first university in the world. Students traveled there from all over the globe to written report Islamic studies, astronomy, languages, and sciences. Standard arabic numbers became known and used in Europe through this university. This is one of import example of the role of women in the advocacy of education and culture. [21]

8.3. Dhayfa Khatun

Dhayfa Khatun, the powerful wife of the Ayyubid ruler of Aleppo al-Zahir Ghazi, was the Queen of Aleppo for six years. She was built-in in Aleppo in 1186 CE. Her male parent was King al-Adel, the brother of Salah al-Din Al-Ayyubi and her blood brother was Rex al-Kamel. She was married to king al-Zahir the son of Salah al-Din. Her son was King Abdul-Aziz. Subsequently her son'south death, she became the Queen of Aleppo as her grandson was but 7 years old. During her half-dozen-year rule, she faced threats from Mongols, Seljuks, Crusaders and Khuarzmein. Dhayfa was a pop queen; she removed injustices and unfair taxes throughout Aleppo. She favored the poor and scientists and founded many charities to support them. Dhayfa was a prominent architectural patron. She established large endowments for the maintenance and operation of her charitable foundations. [22]

Figure xvi. Front cover ofAl-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam by Shaykh Mohammad Akram Nadwi (Interface Publications, 2007). This book is an adaptation of theMuqaddimah or Preface to M. A. Nadwi's multi-volume biographical dictionary in Arabic of the Muslim women who studied and taught hadith. The huge trunk of information reviewed inAl-Muhaddithat is essential to understanding the role of women in Islamic society, their by achievements and future potential.

In improver to her political and social roles, Dhayfa sponsored learning in Aleppo where she founded two schools. The starting time was al-Firdaous Schoolhouse which specialized in Islamic studies and Islamic law, especially the Shafi'i doctrine. Al-Firdaous School was located close to Bab al-Makam in Aleppo and had a teacher, an Imam and twenty scholars, co-ordinate to the construction of the educational arrangement at that time. Its campus consisted of several buildings, including the school, a residential hall for students and a mosque. The second schoolhouse, the Khankah School, specialized in both Sharia and other fields. It was located in Mahalat al-Frafera. Dhayfa died in 1242 at the historic period 59 and was buried in the Aleppo citadel. [23]

8.4. Hürrem Sultan

Hürrem Sultan, besides called Roxelana, was born in yr 1500 to an Ukrainian father. She was enslaved during the Crimean Turks raids on Ukraine during the reign of Yavuz Sultan Selim, and presented to the Ottoman palace. She was the about beloved concubine of Süleyman the Magnificent and became his wife. During her lifetime, Hürrem Sultan was concerned with charitable works and founded a number of institutions. These include a mosque circuitous in Istanbul and the Haseki Külliye circuitous, which consists of a mosque, medrese, school and imaret (public kitchen). She likewise built çifte hamam (double bathhouse with sections for both men and women), two schools and a women's hospital. She as well built iv schools in Mecca and a mosque in Jerusalem. Hürrem Sultan died in April 1558 and lies buried in the graveyard of the Süleymaniye Mosque. [24]

9. Rulers and political leaders

In improver to the roles played by women in Islamic history, as surveyed in the previous sections, we can not finish this introductory article without pointing out the office of some Muslim women as rulers and political leaders in various regions and phases of Islamic culture. We take already referred to Queen Dhayfa Khatun and Princess Hurrem Sultan as patrons of groovy buildings and institutions in the previous section. In the following, nosotros refer to a few outstanding women in management and governance.

9.i. Sitt al-Mulk

In Muslim culture, no woman who had held power had borne the title of caliph or imam. Caliph has been a championship exclusively reserved to a minority of men. Withal, although no woman e'er became a caliph, as such, there have been women who became Sultanas and Malikas (queens). Sitt al-Mulk, the Fatimid Princess in Arab republic of egypt, was one of them. Intelligent and conscientious enough not to violate whatever of the rules and requirements that govern politics in the Islamic social club, and while she carried out most all the functions of caliph, she directed the affairs of the empire quite finer as Regent (for her nephew who was also immature to rule) for few years (1021-1023). She had the title of 'Naib every bit-Sultan' (Vice Sultan).

Sitt al-Mulk (970–1023), was the elder sis of Caliph Al-Hakim. After the death of her father Al-Aziz (975-996), she tried with the help of a cousin to strength her blood brother from the throne, and she became Regent for his son and successor Al-Zahir. She continued to wield influence as an counselor after he came of age, as evidenced by the very generous apanages that came her way.

After the assumption of power, she abolished many of the foreign rules that Al-Hakim had promulgated in his reign, and worked to reduce tensions with the Byzantine Empire over the command of Aleppo, only before negotiations could be completed she died on 5 February 1023 at the age of fifty-two.

9.two. Shajarat al-Durr

Some other Queen begetting the championship of Sultana was Shajarat al-Durr, who gained power in Cairo in 1250 CE. In fact, she brought the Muslims a victory during the Crusades and captured the King of France, Louis Ix.

Shajarat al-Durr (whose proper name means in Standard arabic 'string of pearls'), bore the royal proper name al-Malikah Ismat ad-Din Umm-Khalil Shajarat al-Durr. She was the widow of the Ayyubid Sultan equally-Salih Ayyub who played a crucial role after his death during the 7th Crusade against Egypt (1249-1250). She was regarded past Muslim historians and chroniclers of the Mamluk fourth dimension as existence of Turkic origin. She became the Sultana of Arab republic of egypt on May 2, 1250, marking the end of the Ayyubid reign and the starting of the Mamluk era. She died in Cairo in 1257.

In the course of her life and political career, Shajarat al-Durr, played many roles and held great influence within the court system that she inhabited. She was a military leader, a mother, and a sultana at diverse points throughout her career with neat success until her fall from ability in 1257. Her political importance comes from the menstruation in which she reigned, which included many important events in Egyptian and Middle Eastern history. The Egyptian sultanate shifted from the Ayyubids to the Mamluks in the 1250s. Louis IX of France led the 6th Crusade into Egypt, took Damietta and advanced downward the Nile earlier the Mamluks stopped this ground forces at Mansura. In the midst of this hectic environs, Shajarat al-Durr rose to pre-eminence, reestablished political stability and held on to political ability for seven years in i course or another. [25]

9.3. Sultana Raziya

On the other extremity of the Muslim world and nigh in the aforementioned fourth dimension equally Shajarat al-Durr, some other woman held ability, only this fourth dimension in India. Razia (or Raziyya) Sultana of Delhi took power in Delhi for four years (1236-1240 CE). She was the only woman ever to sit on the throne of Delhi. Razia'due south ancestors were Muslims of Turkish descent who came to India in the 11th century. Contrary to custom, her begetter selected her, over her brothers, to be his successor. Afterwards her begetter's death, she was persuaded to step down from the throne in favour of her stepbrother Ruknuddin, but, opposed to his rule, the people demanded that she get Sultana in 1236.

She established peace and gild, encouraged trade, congenital roads, planted trees, dug wells, supported poets, painters, and musicians, constructed schools and libraries, appeared in public without the veil, wore tunic and headdress of a human. State meetings were often open to the people. Yet, she made enemies when she tried to eliminate some of the discriminations against her Hindu subjects.

Jealous of her attention to i of her advisors, Jamal Uddin Yaqut (not of Turkish blood), her governor, Altunia, rebelled. Razia's troops were defeated, Jamal was killed in boxing, Razia was captured and married to her conqueror in 1240. One of her brothers claimed the throne for himself, Razia and her new husband were defeated in battle where both died. [26]

Effigy 17. Front cover ofAl-Mu'allifat min al-nisa' wa-mu'allataftuhunna fi al-tarikh al-islami past Muhammad Khayr Ramadhan Yusuf (Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm, 1412 H).

Firishta, a 16th-century historian of Muslim rule in India, wrote about her: "The Princess was adorned with every qualification required in the ablest kings and the strictest scrutinizers of her actions could find in her no error, but that she was a adult female. In the fourth dimension of her father, she entered deeply into the affairs of government, which disposition he encouraged, finding she had a remarkable talent in politics. He in one case appointed her regent (the i in control) in his absenteeism. When the emirs (military advisors) asked him why he appointed his daughter to such an part in preference to and so many of his sons, he replied that he saw his sons giving themselves up to wine, women, gaming and the worship of the wind (flattery); that therefore he thought the government too weighty for their shoulders to bear and that Raziya, though a woman, had a man'due south head and heart and was better than twenty such sons." [27]

9.4. Amina of Zaria

In Muslim Africa, several women excelled in various fields. Amongst them, Queen Amina of Zaria (1588-1589). She was the eldest daughter of Bakwa Turunku, who founded the Zazzau Kingdom in 1536. Amina came to power between 1588 and 1589. Amina is generally remembered for her violent military exploits. Of special quality is her brilliant military strategy and in item engineering skills in erecting nifty walled camps during her various campaigns. She is mostly credited with the building of the famous Zaria wall.

Amina of Zaria, the Queen of Zazzua, a province of Nigeria now known as Zaria, was born effectually 1533 during the reign of Sarkin (rex) Zazzau Nohir. She was probably his granddaughter. Zazzua was ane of a number of Hausa city-states which dominated the trans-Saharan trade after the collapse of the Songhai empire to the west. Its wealth was due to trade of mainly leather appurtenances, cloth, kola, common salt, horses and imported metals.

At the age of 16, Amina became the heir credible (Magajiya) to her mother, Bakwa of Turunku, the ruling queen of Zazzua. With the championship came the responsibility for a ward in the city and daily councils with other officials. Although her mother'south reign was known for peace and prosperity, Amina besides chose to learn war machine skills from the warriors.

Queen Bakwa died around 1566 and the reign of Zazzua passed to her younger brother Karama. At this time Amina emerged every bit the leading warrior of Zazzua cavalry. Her military achievements brought her neat wealth and power. When Karama died after a ten-yr dominion, Amina became queen of Zazzua.

She prepare off on her start military trek iii months after coming to ability and connected fighting until her death. In her thirty-four year reign, she expanded the domain of Zazzua to its largest size always. Her principal focus, however, was not on annexation of neighbouring lands, merely on forcing local rulers to have vassal status and permit Hausa traders safe passage.

She is credited with popularizing the earthen city wall fortifications, which became characteristic of Hausa metropolis-states since then. She ordered edifice of a defensive wall around each campsite that she established. Later on, towns grew within these protective walls, many of which are still in existence. They are known as "ganuwar Amina", or Amina'south walls. [28]

Effigy 18. Painting of Queen Amina of Zaria by Floyd Cooper (Source)

9.5. Ottoman women.

We end this section with a annotation on Ottoman women, a field of investigation that began to attract the attention of scholars. In the 16thursday and 17th century, harems played an important part in the authorities of the Ottoman Empire. [29] Unlike the mutual perception, the Harem was an administrative centre of authorities, run by women only. [30] This is a field of research in which a systematic investigation volition be rewarded by great results.

10. Miscellanea

In addition to the specialties and social roles mentioned above, other fields knew the contribution of Muslim women. Ii examples show how much a serious investigation will progress our knowledge of their contribution. In chemical science, historical sources quote the proper name of Maryam Al-Zinyani. Some scholars suggested that Maryam Al-Zinyani is Maryam bint Abdullah al-Hawary who died in year 758 CE in Kairouan. In addition to writing poetry, Maryam was skilled in chemistry. [31]

11. By way of a conclusion

Muslim women participated with men in constructing Islamic culture and civilization, excelling in poetry, literature and the arts. In addition, Muslim women have demonstrated tangible contributions in mathematics, astronomy, medicine and in the profession of health care. Nonetheless, the study of the role of Muslim women in the advocacy of science, applied science and medicine is difficult to certificate every bit there are only scant mentions of it. New calorie-free might arise from the study of not yet edited manuscripts. At that place are about 5 million manuscripts in archives around the world. Only about fifty,000 of them are edited and nearly of these are not near science. Editing relevant manuscripts is indeed a strategic result for discovering the role of Muslim women in science and civilization.

12. Bibliography

- Abdel Mahdi, Abdeljalil, "Al-Mar'a fi bilad al-sham fi al-'asrayn al-ayyubu wa-'l-mamluki muta'allima wa-mu'llima", Majallat majma' al-lugha al-'arabiya al-urduni, no. 38, Jan-June 1999.

- Abou Chouqqa, Abd al-Halîm Aboû Chouqqa, Dabbak, Claude, Godin, Asmaa, Encyclopédie de la Femme en Islam, Al Qalam, 2000-2007, 6 vols.

- Al-Hassani, Salim, Lecture: Cracking Men and Women of Science in Muslim Heritage (declaration of a lecture, 21 November 2006).

- Al-Hassani, Salim (chief editor), 1001 Inventions: Muslim Heritage in our World, Manchester: Foundation for Scientific discipline, Technology and Civilisation, 2006.

- Al-Heitty, Abd al-Kareem, "The Collection and Criticism of the Work of Early Arab Women Singers and Poetesses", Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean (Routledge), vol. 2, no. 1, 1989, pp. 43-47.

- Al-Malaqi, Abu 'l-Hasasan Ali b. Muhammad al-Ma'rarifi, Al-hada'iq al-ghanna' fi akhbar al-nisa', edited by 'A'ida al-Taybi, Tunis/Tripoli: Al-Dar al-'arabiya li-'l-kitab, 1978.

- Al-Munajjid, Salah al-Din, "Mā 'ullifa 'an al-nisā'" (what was written about women), Majallat al-Majma' al-'ilmī al-'Arabī, vol. 16, 1941, pp. 212-19.

- Al-Munajjid, Salah al-Din, Jamal al-Mar'ah 'inda 'fifty-'Arab (Women'southward Dazzler among the Arabs), Beirut: Dar al-kitab al-jadid, 1969.

- El-Azhary Sonbol, Amira (editor), Beyond The Exotic: Women's Histories In Islamic Societies, Syracuse University Press, 2005.

- El-Azhary Sonbol, Amira, "Menses 500-800, Women, Gender and Islamic Cultures (6th-9th Centuries)", in Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures, Full general Editor: Suad Joseph, 5 vols., Leiden-Boston: E. J. Brill, 2003. For an online preview, click here.

- El-Azhari, Taef Kamal, "Dayfa Khatun, Ayyubid Queen of Aleppo 634-640", Annals of Nihon Association for Middle E Studies, no. 15, 2000, pp.27-55.

- Finkel, Caroline, Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire, New York: Basic Books, 2006.

- [FSCT], Women and learning in Islam (brusque quotation from Southward.P. Scott, The History of the Moorish Empire in Europe, J.B. Lippincott Visitor, 1904, 3 vols., pp.447-48 (published 21 July 2002).

- FSTC, Representing Islam and Muslims in the Media: An Bookish Debate (published 17 December, 2008). Study on the international conference Representing Islam: Comparative Perspectives (5-6 September 2008) organised jointly by the Universities of Manchester and Surrey. See section half dozen. Women and Islam.

- FSTC, Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and University (published 20 Oct 2004).

- Hambly, Gavin (editor), Women in the Medieval Islamic Earth, New York: St. Martin'due south Press, Palgrave Macmillan, 1998, reprinted 1999.

- Hanne, Eric J., "Women, Power, and the Eleventh and Twelfth Century Abbasid Court", Hawwa (Brill), vol. 3, no. i, 2005, pp. fourscore-110.

- Hassan, Farkhonda, "Islamic Women in Scientific discipline", Scientific discipline, vol. 290, no. 5489, half-dozen October 2000, pp. 55-56.

- Humphreys, Stephen R., "Women as Patrons of Religious Architecture in Ayyubid Damascus", Muqarnas, BRILL Vol. 11, (1994), pp. 35-54.

- Joseph, Suad (General Editor), Encyclopaedia of Women and Islamic Cultures, Associate Editors Afsaneh Najmabadi, Julie Peteet, Seteney Shami, Jacqueline Siapno and Jane I. Smith. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006, 5 vols.

- Ingeborg, Otto, and Schmidt-Dumont, Marianne, Frauen in den arabischen Ländern: eine Auswahlbibliographie [Women in the Arab countries: a selected bibliography], Dokumentationsdienst Vorderer Orient: Reihe A, 27, Hamburg: Deutsches Übersee-Institut, Übersee-Dokumentation, Referat Vorderer Orient, 2000.

- Kalmbach, Hilary, "Social and Religious Change in Damascus: I Case of Female Islamic Religious Authorization, British Journal of Heart Eastern Studies, vol. 35, Issue 1 Apr 2008 , pages 37 – 57.

- Kasule, Omar Hasan, "Rufaidah bint Sa'ad: Historical Roots of the Nursing Profession in Islam [Abstruse of a paper presented at the tertiary International Nursing Conference "Empowerment and Health: An Calendar for Nurses in the 21st Century" held in Brunei Dar equally Salam 1st-4th Nov 1998].

- Keddie, Nikki R., "The Past and the Present of Women in the Muslim World", Journal of World History, vol. 1, no. ane, leap 1990, pp. 77-108.

- Kimball, M. R., Von Schlegell, B. R. & Schlegell, B. R. von. Muslim women throughout the world: a bibliography, Boulder: Rienner, 1997.

- Lachiri, Nadia, and Moral, C. del, Bibliografía para el estudio de las mujeres en el mundo árabe medieval, con especial referencia a Al-Andalus Árabes, judías y cristianas: mujeres en la Europa medieval normal, edited past C. del Moral, Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1993, pp. 225-236.

- Lev, Yaacov, "Charity, pious endowments and royal women in Medieval Islam", in Continuity and Change in the Realms of Islam: Studies in Honour of Professor Urbain Vermeulen, edited by K. D'hulster and J. Van Steenbergen, Leuven/Paris: Dudley/Peeters, 2008, pp. 413-422.

- Mernissi, Fatima, 'Women in Muslim History: Traditional Perspectives and New Strategies' in S. Jay Kleinberg (ed.) Retrieving Women'due south History: Changing Perceptions of the Part of Women in Politics and Society, (Oxford: Berg, 1988), pp. 338-355. Reproduced in Women and Islam: Critical Concepts in Sociology, edited by Haideh Moghissi September 2004 Routledge, pp. 37-52.

- Montgomery Watt, William, "Women in the Primeval Islam", Studia missionalia (Editrice Pontificia Universita Gregoriana, Roma), vol. 40, 1991, pp. 162-173.

- Murphy, Claire Rudolf et al.: Daughters of the Desert: Stories of Remarkable Women from Christian, Jewish and Muslim Traditions. Skylight Path, 2005.

- [Nadwa], Dawr al-mar'a al-'arabiya fi al-haraka al ('ilmiya, proceedings of the colloque organised by the Markaz ihya' al-turath al-'ilmi al-'arabi wa-'l-itihad al-'am li-nisa' al-'Iraq, Baghdad: Publications of the University of Baghdad, 1988. Includes specially: Saleh Mahdi Abbas, "Athar al-mar'a al-baghdadiya fi fi 'l-haraka al-'lmiya"; Khudhayr 'Abbad al-Manshadaoui, "'Alimat al-riyyadhiyat al-'arabiya 'Amat Alwahid Al-Baghdadiya".

- Nadwi, Mohammad Akram, Al-Muhaddithat: The Women Scholars in Islam, Oxford: Interface Publications, 2007.

- Peirce, Leslie P., The Majestic Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire (Studies in Middle Eastern History), Oxford University Printing, 1993.

- Prymak, Thomas M., "Roxelana: Wife of Suleiman the Magnificent," Nashe zhyttia/Our Life (New York), vol. 52, no. 10, 1995, pp. fifteen-20.

- Pudioli, Maria Cristina, "Donne dell'Islam: una ricerca bibliografica nelle biblioteche di Bologna", Ricerche Bibliografiche: Centro Amilcar Cabral (Bologna: Il Nove), no. 17, 1998.

- Rashid, Sa'd ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz, Darb Zubaydah: the pilgrim road from Kufa to Mecca. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Riyadh University Libraries, 1980.

- Rassool, Thousand. Hussein, "The Crescent and Islam: Healing, Nursing and the Spiritual Dimension. Some Considerations towards an Understanding of the Islamic Perspectives on Caring", Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 32, no. six, 2000, pp. 1476-1484.

- Shahraz, Qaisra Book Review of 'Ottoman Women – Myth and Reality' by Asli Sancar.

- Sayyah Mesned Alesa, Muhammad, El Estatus de la mujer en la sociedad arabo-islamica medieval entre oriente y occidente, Doctoral thesis University of Granada, 2007.

- Sari, Nil, Women Dealing with Health during the Ottoman Reign.

- Singer, Amy, "The Mülknames of Hürrem Sultan's Waqf in Jerusalem", in Muqarnas Fourteen: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World. Edited by Gülru Necipoglu. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1997, pp. 96-102. Online here.

- Tabbaa, Yasser, "Dayfa Khatun: Regent Queen and Architectural Patron," in Ruggles, Women, Patronage, and Cocky-Representation, edited by D. Fairchild Ruggles, State University of New York Press, 2000, pp. 17-34.

- Tazi, Abdeladi, Al-Mar'a fi tarikh al-gharb al-islami [Women in the history of the Islamic west]. Casablanca: Le Fennec, 1992.

- Tucker, Judith Eastward., 'Women in the Middle Eastward and North Africa: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries' in Guity Nashat and Judith Tucker (eds.) Women in the Heart East and Due north Africa, (Indiana University Press, 1999), pp. 101-31.

- Waddy, Charis, Women in Muslim History, London and New York: Longman Group, 1980.

- Wahba, Taoufiq, Dawr al-mar'ah fi al-mujtama' al-islami. Riyadh: Dar al-liwa', 1978.

- Yermolenko, Galina, "Roxelana: The Greatest Empress of the East," The Muslim World, vol. 95, no. ii, 2005, pp. 231-48.

References

[1] Encounter Michael A. B. Deakin, "Hypatia and Her Mathematics", The American Mathematical Monthly, March 1994, vol. 101, No. 3, pp. 234-243; 50. Cameron, "Isidore of Miletus and Hypatia of Alexandria: On the Editing of Mathematical Texts", Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies vol. 31 (1990), pp. 103-127; I. Mueller, "Hypatia (370?-415)", in L. S. Grinstein and P. J. Campbell (eds.), Women of Mathematics (Westport, Conn., 1987), pp. 74-79; Bryan J. Whitfield, The Dazzler of Reasoning: A Reexamination of Hypatia of Alexandra; O'Connor, John J. & Robertson, Edmund F., "Hypatia of Alexandria", from MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive; Hypatia of Alexandria: A woman earlier her time, The Woman Astronomer, 11 November 2007 (accessed 12.05.2008); "Hypatia of Alexandria" (from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Resources on Hypatia (booklist and classroom activities).

[2] Okasha El-Daly, Egyptology: the Missing Millennium. Ancient Arab republic of egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings. London: UCL Printing, 2005.

[iii] See the biography of Aishah bint Abi Bakr (Academy of Southern California: USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts); Montgomery Watt, "Ā'isha Bint Abī Bakr", Encyclopedia of Islam, Brill, vol. 1, p. 307; Amira Sonbol, "Menstruum 500-800, Women, Gender and Islamic Cultures (6th-9th Centuries)", in Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures, Full general Editor: Suad Joseph, half-dozen vols. Leiden-Boston: East. J. Brill, half-dozen vols., 2003. See an online preview here.

[4] Sabiha Gökçen, Atatürk'le Bir Ömür (A Life with Atatürk) (in Turkish), Istanbul: Altin Kitaplar, 2000. See as well Sabiha Gokcen (1913-2001), Pioneer Aviatrix.

[5] Private communications with Qassim Al-Samarrai, Professor of Palaeography, Leiden, Holland.

[6] Oxford: Interface Publications, 2007 (hardcover and paperback).

[7] Over the last few years Dr. Nadwi has, on several occasions and in dissimilar cities, given an introductory talk on the public say-so and achievements of the women scholars of hadîth. Ane of those talks was given in New York. Carla Power, a London-based journalist attended that occasion, and has since reflected upon Akram Nadwi's piece of work in a magazine commodity published by the New York Times (25 Feb 2007): come across A Secret History. A follow-upward article, washed after an interview with the author in Oxford, was published in the London Times, 14 April 2007. For another article, also after an interview with Akram Nadwi, this one in Arabic, go here. Read also a PDF file (17 pp.) of Akram Nadwi'southward introductory talk on the women scholars in Islam, click here.

[8] Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley, Muslim Women: A Biographical Dictionary, Ta-Ha Publishers, 2004.

[9] Ibid, introduction.

[10] Waddy Charis, Women in Muslim History, London and New York: Longman Grouping, 1980, p. 72.

[11] R. Jan, "Rufaida Al-Asalmiy, The first Muslim nurse", Prototype: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 1996 28(3), 267-268; Thousand. Hussein Rassool, "The Crescent and Islam: Healing, Nursing and the Spiritual Dimension. Some Considerations towards an Understanding of the Islamic Perspectives on Caring", Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000, 32 (six), 1476-84; Omar Hasan Kasule, "Rufaidah bint Sa'advertizing: Historical Roots of the Nursing Profession in Islam; History of Nursing in Islam (compiled past Sarah Miller); Rufaidah bint Sa'advertisement Founder of the Nursing Profession in Islam.

[12] Run across the manufactures Muslim Women in History and Al-Shifaa bint Abdullah al Qurashiyah al Adawiyah.

[13] Abdel-Hamid 'Abd Rahman Al-Sahibani, Suwar min Siyar al-Sahābiyāt, Riyadh: Dar Ibn Khazima, 1414 H, p. 211; 'Umar Kahala, A'lam al-nisa', Damascus, 1959, vol. v, p. 171.

[14] G. Bademci Gulsah, "First illustrations of female person "Neurosurgeons" in the fifteenth century by Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, Neurocirugía (Sociedad Española de Neurocirugía, Murcia, Spain), Apr 2006, vol. 17, no. two, pp. 162-165. The book was edited several times, encounter Serefeddin Sabuncuoglu, Kitabul Cerrahiyei Ilhaniye, Istanbul, Kenan Basimevi, 1992, and Ankara, Turk Tarih Kurumu Yayinlari, 1992.

[xv] Al-Khatib Baghdadi, Tarikh Baghdad, Cairo: Happiness Press, 1931, vol. 6, p. 370. To read this section online: click here.

[16] Abu 'l-Faraj Abdurahman b. Ali ibn al-Jawzi, Al-muntazam fi 'l-tarikh, Haydarabad: Da'irat al-ma'arif al-uthmaniya, 1359, vol. 14, pp. 161-202; this section is online at: click here; Haji Khalifa, Kashf al-Zunun an 'Asami al-Kutub wa al-Funun, Istanbul: al-Ma'aref, 1941.

[17] Samuel P. Scott, The History of the Moorish Empire in Europe, Philadelphia & London: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904, vol. 3, p.447; quoted in [FSTC], Women and learning in Islam.

[18] Ibn al-Nadim, Kitab al-Fihrist, edited by Risha Tajaddud, Tehran, Maktabat al-Aasadi, 1971, p. 342-343.

[19] R. Khanam (editor), Encyclopaedic ethnography of Eye-East and Fundamental Asia, New Delhi: Global Vision Publishing, 2005, vol. 1, p. 291. Run into also on the Banu 'Ijl tribe Fred McGraw Donner, "The Bakr B. Wā'il Tribes and Politics in Northeastern Arabia on the Eve of Islam", Studia Islamica, No. 51 (1980), pp. v-38.

[20] See Eric J.Hanne, "Women, Power, and the Eleventh and 12th Century Abbasid Court", Source: Hawwa (Brill), vol. iii, No. 1, 2005, pp. 80-110; Sa'd ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz Rashid, Darb Zubaydah: the pilgrim road from Kufa to Mecca. Riyad, Saudi Arabia: Riyad University Libraries, 1980; Women Edifice Masjids; and Zubaydah the Empress.

[21] FSTC, Midweek 20 October, 2004, "Al-Qarawiyyin Mosque and Academy"; Abdeladi Tazi, Al-Mar'a fi tarikh al-gharb al-islami, Casablanca: Le Fennec, 1992; "University of Al-Karaouine", in Wikipedia.

[22] Ibn al-'Adīm, Zubdat Al-Halab fi Tareekh Halab, Dar al-kutub al-'ilmiya, 1996; Terry Allen, Madrasah al-Firdaus, in Ayyubid Architecture, Occidental, CA: Solipsist Press, 2003 [accessed 12.05.2008]; Yasser Tabbaa (1997), Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo. The Pennsylvania State University Printing, pp. 46-48,142,168-171; Abdul Qader Rihawi (1979), Arabic Islamic Architecture in Syria, Damascus: Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, p. 138; Manar Hammad, (2003), "Madrasat al-Firdaws: Paradis Ayyubide de Dayfat Khatun" (Unpublished newspaper). Available online: click here.

[23] Yasser Tabbaa, "Dayfa Khatun: Regent Queen and Architectural Patron," in Ruggles, Women, Patronage, and Self-Representation, 17-34; Taef Kamal el-Azhari, ": Dayfa Khatun, Ayyubid Queen of Aleppo 634-640", Annals of Nippon Association for Middle Due east Studies No. xv 2000.

[24] Thomas Thousand. Prymak, "Roxolana: Married woman of Suleiman the Magnificent," Nashe zhyttia/Our Life, LII, 10 (New York, 1995), 15-20; Galina Yermolenko, "Roxolana: The Greatest Empresse of the Eastward," The Muslim Globe, 95, 2 (2005), 231-48; "The Islamic World to 1600: Roxelana" (University of Calgary); Amy Vocalizer 1997. "The Mülknames of Hürrem Sultan'south Waqf in Jerusalem", in Muqarnas XIV: An Annual on the Visual Civilization of the Islamic World. Edited by Gülru Necipoglu. Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 96-102. Online hither. Encounter also "Roxelana" in Wikipedia, the gratis encyclopedia.

[25] See on Shajarat al-Durr the classic work of Götz Schregle Die Sultanin von Ägypten: Sagarat ad-Durr in der arabischen Geschichtsschreibung und Literatur (Wiesbaden, O. Harrasowitz, 1961) and the recent articles past David J. Duncan, "Scholarly Views of Shajarat Al-Durr: A Demand for a Consensus" published in Chronicon vol. 2 (1998), no. four: pp. 1-35 and in Arab Studies Quarterly (ASQ), vol. 22, January 2000. Read as well Amira Nowaira, Shajarat Al-Durr, From the Harem to Highest Part (9 Jun 2009).

[26] Sultana Razia by Lyn Reese in Her Story: Women Who Changed the World, edited by Ruth Ashby and Deborah Gore Ohrn, Viking, 1995, pp. 34-36.,

[27] Quoted in "Muslim Women Through the Centuries" by Kamran Scot Aghaie, Nat'50 Center for History in the Schools, Academy of California at Los Angeles,1998, p. 32.

[28] Danuta Bois, Amina Sarauniya Zazzua (1998). Encounter also Amina Zazzua profile by Denise Clay in Heroines. Remarkable and Inspiring Women/An Illustrated Anthology of Essays past Women Writers (New York: Crescent Books, 1995) and Queen Amina – Queen of Zaria.

[29] Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire. Hardcover: 704 pages. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

[30] Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire (Studies in Center Eastern History), Oxford University Printing, 1993.

[31] Hasan Hosni 'Abd-Wahab, Shahīrāt Tūnusiyāt, Tunis, 1934.

Source: https://muslimheritage.com/early-women-of-science/

0 Response to "Prof Lubna Riyadh Abdul Jabarcollege of Arts Baghdad University"

Post a Comment